Another Academy

First published in a Italian translation by Giovanna Di Lello, in Avvenire (Milan, August 18, 2022)

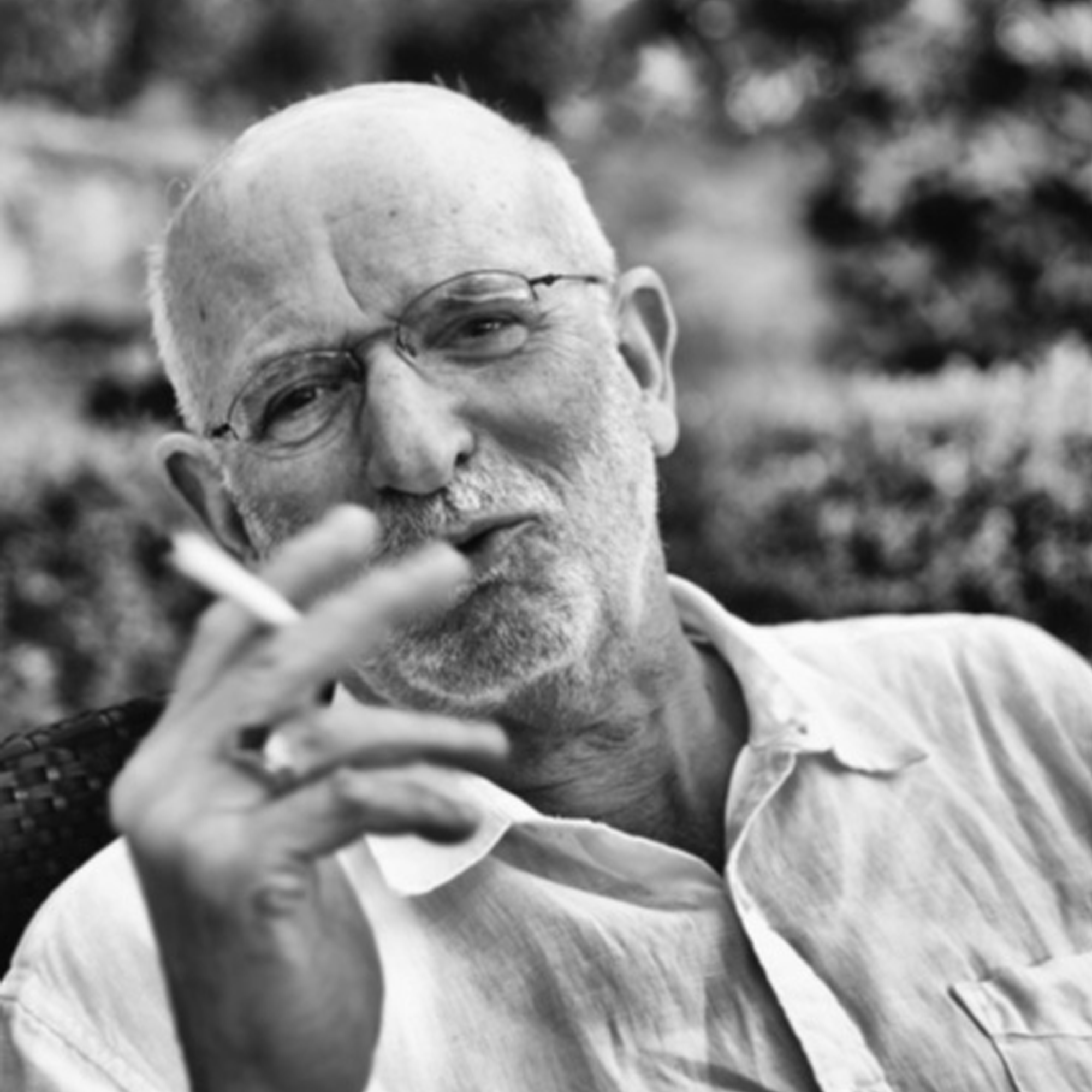

ESSAY by Paul Vangelisti In 1970, at the end of my second year of graduate school, I met Charles Bukowski. I had read his 1967 book of poetry Days Run Away like Wild Horses, Over the Hills and the 1969 collection of articles, Notes of a Dirty Old Man (not to be confused with a later, and far less interesting collection from City Lights). Bukowski’s poetry offered my generation (Bukowski was born a year before my father) an alternative to the essentially academic contest between the Black Mountain and Deep Image schools of poetry, the breathers

and dreamers,

as Los Angeles poet Bert Meyers called them.

I enjoyed listening to Bukowski’s stories of how he came to writing, from an essentially immigrant, working class household. After only a year or so at Los Angeles City College, he decided he would write fiction and began looking around for models. In those days, the end of the thirties and beginning of the forties, he recalled falling under the influence of Knut Hamsen’s Hunger and Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, as well as some Hemingway stories. He then mentioned a writer I was completely unfamiliar with, John Fante, and the two books that had captured his young mind, Wait Until Spring, Bandini and Ask the Dust.

Both books, I soon discovered, were out-of-print. I found copies at the Central Library, in their original (1938 & 1939) hardback editions, and brought them to Bukowski’s duplex on De Longpre. We noticed that both books were in good condition, as they hadn’t been checked out in over twenty years. Ask the Dust was my particular favorite, as it was Bukowski’s. Soon, after returning Wait Until Spring, Ask the Dust became for us almost a cult object. In fact, some fifty years later, I don’t think we ever returned the only copy of Fante’s classic to the downtown library.

This was more than 50 years ago. As Chandler, Fante and Bukowski knew it, Bunker Hill is certainly no more. No more Court Street, bulldozed to build the Bunker Hill Towers and later the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). Down the hill on Temple Street, in name only is the shabby tourist trap that’s now the “Old Pueblo.” Long gone, however, is that remarkable few blocks of 20th century L.A., the Mexican cafeteria where Arturo Bandini used to go and moon over his beautiful Mexican waitress.

All this made a curious impression when Bukowski told me a story about his early devotion to Fante. It was just before the War when Bukowski began thinking of meeting his idol, a man alone writing in a room on downtown Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill. Bunker Hill was then all rooming houses,

in the words of Raymond Chandler, old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town… [where] haggard landladies bicker with shifty tenants

(High Window, 1942). Somehow the young Bukowski located Fante’s decrepit rooming house on Court Street, immortalized in Ask the Dust, and would spend nights, standing in the empty lot below, as Bukowski told it, looking up at the lit, open window where his master was drinking and typing. Once in a while, a bottle would come flying out of the window. He’d take the relic back to his parents’ house where, in his bedroom, he’d created a shrine to Fante. There, in sight of the liquor bottle shrine, Bukowski said that he’d sit and try to write fiction.

As I write this in the late afternoon on a hillside in the Magra River valley, I can’t help but be aware of all that’s passed. Of Bandini and his walks in worn-out shoes down to Alvera Street there only remain books and memories, and at this time of day, perhaps, that will do.

Paul Vangelisti

Bagnone, 2022