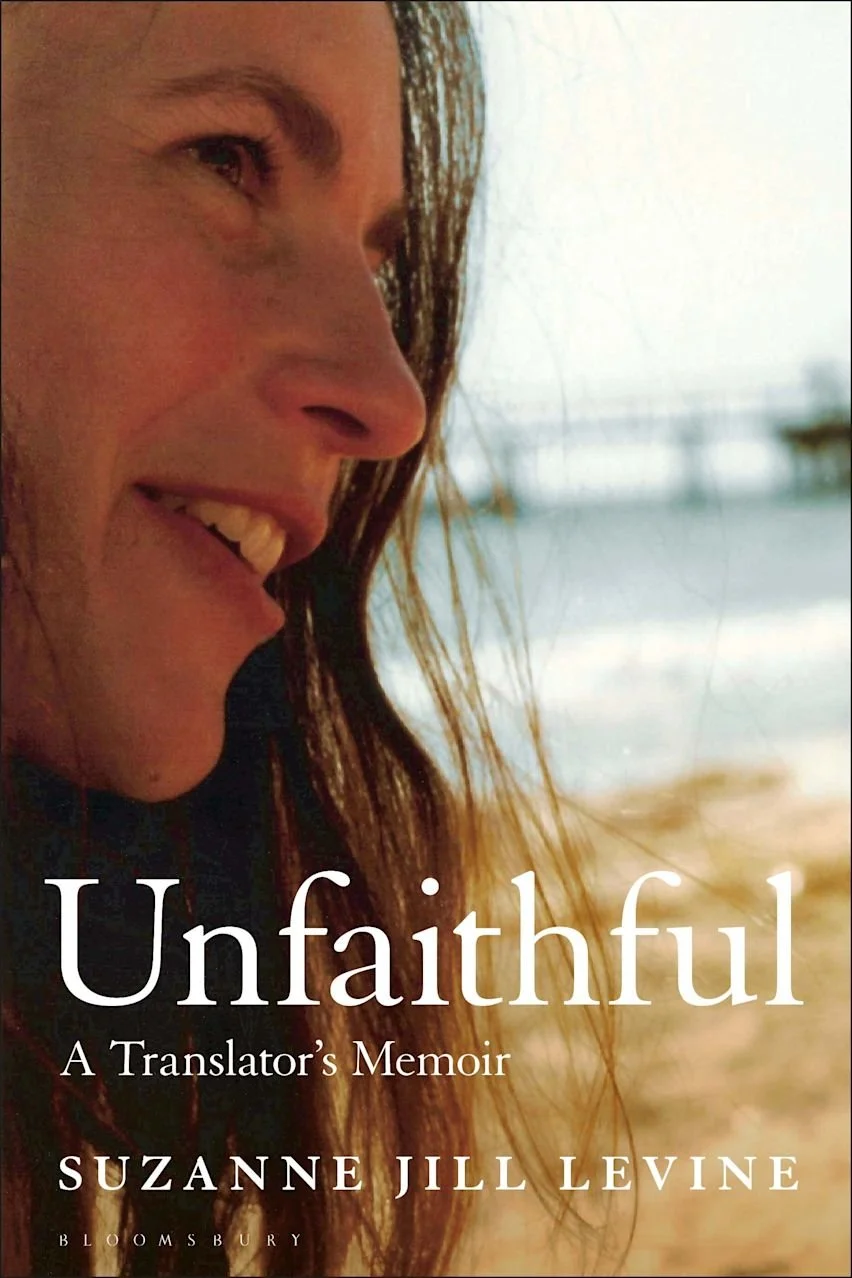

Suzanne Jill Levine’s Unfaithful: A Translator’s Memoir

Unfaithful: A Translator’s Memoir

Suzanne Jill Levine

Bloomsbury Academic, 2025

REVIEW by Paul Vangelisti As the translator of Manuel Puig, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Severo Sarduy, Guillermo Cabrera Infante and Jose Donoso, among others, Levine’s career, beginning in the early seventies, has been nothing short of exemplary. A distinguished professor of Spanish at the University of California, Santa Barbara, as well as a tireless advocate for translation, Levine has been a notable influence on several generations of writers and translators.

Foremost among her concerns in Unfaithful is the notion of closelaboration, through which the translator came to understand that certain of her authors, with whom she has cultivated close friendships over the years, were themselves “keen to show readers ‘what gets lost’ is merely the flip side ‘of what gets gained.’” So that, as Levine notes, translation may be a solitary pursuit but not a lonely one. She claims that as a translator she has always sensed the writer presence, there with her, engaging her in a dialogue, and “how what seems a departure from the text is a way into the text.”

Moreover, Levine underscores that in Unfaithful she wishes to draw attention to what she calls a “deeply personal view of the translator,” focusing on herself as protagonist, as if she were a “picaresque character” in the adventure that comes to be called a work of fiction. Unlike the relative absence of context in translating certain contemporary poetry, where the word (or language) rebukes common definitions of writing, Levine presents the translator of fiction needing an “intimate closeness” with what surrounds the text, as well as, in some cases, with the authors themselves.

This memoir is comprised of a series of extended anecdotes, from her familial beginnings in Manhattan, to her exchange student days in Madrid, to the ferment of 1968 and her baptism in the literary life at Columbia, and finally to the start of the Latin American Boom with the chapter, ”Swinging London with Cabrera Infante,” one of the most evocative in the book. There follow two equally entertaining chapters which reveal the translator’s development as her own protagonist in the works of fiction she would undertake: “The 1970s: The Buenos Aires Affair in New York” and “With Bioy in the Bois de Boulogne.”

The second part of the memoir, in which Levine turns somewhat more inward, is epitomized for me by her piece reflecting on the sudden death of Carlos Fuentes, “Carlos Fuentes on Central Park West.” For Levine and for his fellow Spanish American novelists, Fuentes’ death was unavoidably the end of an era. Essential to this passing is the awareness that Levine notes, in the words of Mario Vargas Llosa: “I see the Mexican Carlos as the first active and conscious agent of the internationalization of the Spanish American novel in the 1960s.”

For the pleasure of repeating her compelling prose, and to avoid my less than exemplary paraphrase, I cite from Levine’s “Afterword”:

The translator is a lover … a scenario in which there is, inevitably, a degree of unfaithfulness and distance. We need to understand that what may appear as a form of betrayal allows for the translator’s subjectivity and her own voice to emerge in close dialogue with the original. We need to

understand that the idea of fidelity is utopic, and that no literary translation can ever be completely faithful to the original.

Levine is careful to emphasize that the best translations serve a dual function, as a critical interpretation of the text in question, and as a work of art in a new form that reproduces or reinvents the original.

Unfaithful: A Translator’s Memoir needs no further comment, except to say: read it!